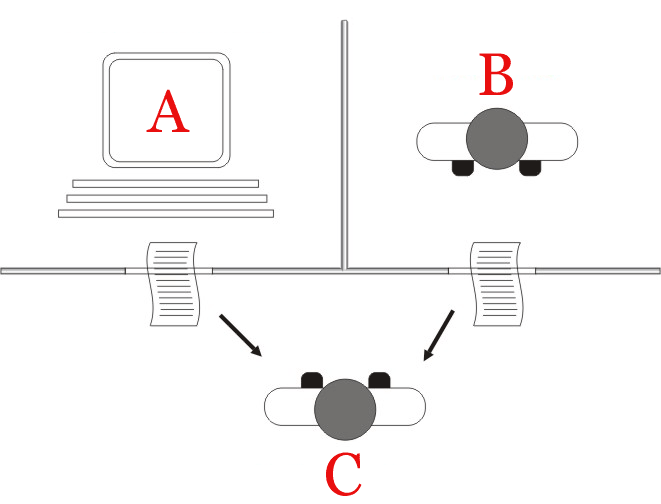

Alan Turing in "Computing Machinery and Intelligence" asks us to play a game. The game requires two players, a man and a woman – A and B – and an additional interrogator. The goal of the players is to convince the interrogator in a different room that they are a woman or man via written messages, while the interrogator asks questions so as to make a guess on who is whom.

To make his point, Turing then asks us to exchange one of the players with a computing machine and wonders if it would be able to play the game as well as a human.

“What will happen when a machine takes the part of A in this game? ” he asks.

Will the interrogator decide wrongly as often when the game is played lie this as he does when the game is played between a man and a woman? Thus, Turing implies, if it is possible that a computing machine play the game sufficiently well to convince the interrogator that they are a human man or woman, then perhaps we are given license to say that the machine thinks.

While the original question asks if a computing machine can “think,” the question has now been replaced by another that only asks if the interrogator may be convinced by a machine sufficiently enough for the interrogator to believe (perhaps, be fooled) it is human.

Indexically, the question has also changed. It is no longer about whether the machine can think; but if it can induce a sufficient experience in the interrogator to be convinced that he is in dialogue with a human. The outcomes are measured by entirely different intuitions. To achieve this goal, the computer need not be thinking at all, but need only provide the sufficient appearance that it may be so. That is, the success markers of AI is dependent on the response of the observer as a matter of subjective agreement or taste. An aesthetic judgement.

Broadly construed, current artificial intelligence research works in this manner: a computational model of varying sorts is built using a broad scope of data and inputs and its outputs are judged by human observers against the criteria: does this seem human-like? Progress of AI research is thus measured by the gradual increase in perceived approximation of the criteria of appearing human. It is the critique and analysis of a subjective impression occurring in a person of an external expression, viewed through layers of personal value systems ultimately relying on taste, feeling, and sentiment, focused on the perception of humanness in a created object. I argue that if that is the predominant metric for the success of AI systems, then AI research is an aesthetic movement.

Its goal is not to be human or even close-to-human, but to convince a sufficient number of people that it seems so. AI research is really the study of the collective meta-response of the subjective experiences we have when we interact with the outputs of computational systems; a critique of an objet d’art. When Turing asks “can a machine think?” he lays no claim to any objective and external success criteria for this question to be successfully answered. Rather, he defaults to the idea of whether not a person may be convinced that they are talking to a real person. Thus, he asks a question about matters of taste, not a question of technological advancement or matters of propositional truth.

Turing and the AI research industry’s appeal to our subjective sensibilities appears to be proposing that the Mona Lisa could be considered real if enough people are fooled into thinking she is real. But plainly, this is not in line with reality. We are simply and subjectively appraising its capacity to imitate some small subset of human capacity. The appearances, not the object-in-itself, independent of observation.

GPT-3, in a closed room, would mindlessly output text that is of statistical significance, endlessly cycling through its linguistic probabilities, generating text on a screen until someone with the gift of self-consciousness decides to turn it off [1].

1. Shout out to the late, great Roger Scruton.